Aspirin for Primary Prevention: What We Thought, What We Know Now, and What Still Matters

For decades, low-dose aspirin has been considered a simple and generally harmless way to reduce the risk of heart attack and stroke. As people aged, many were advised to take it "just in case", even if they had never had cardiovascular disease (CVD) such as heart attack or stroke.

In recent years that advice has changed. Not subtly, but fundamentally.

Aspirin remains one of the most misunderstood medications in cardiovascular prevention. Some people are still taking it unnecessarily. Others have stopped it abruptly and are confused by mixed messages. And many are asking a reasonable question: if aspirin was once considered protective, what happened?

To answer that, we need to look carefully at the evidence. Aspirin lowers clot-related events but increases bleeding risk. The decision to use aspirin comes down to weighing its ability to reduce cardiovascular events against its risk of causing bleeding.

Any decision to use aspirin involves balancing a reduction in cardiovascular events against an increased risk of bleeding.

Why Aspirin Seemed Like a Good Idea

Aspirin reduces platelet aggregation and lowers the risk of clot formation. Most heart attacks come from blood clots sticking to plaque in the heart arteries. In people who have already had a heart attack or stroke, this antithrombotic effect clearly saves lives.

This is known as secondary prevention, and aspirin remains a cornerstone of care. After a heart attack, most patients should take aspirin long term because the risk of recurrent cardiovascular events is high.

The assumption for many years was that this benefit would extend to people without established cardiovascular disease. If clots cause heart attacks, and aspirin reduces clots, then surely aspirin could prevent first events too.

Early studies supported that view, but they were conducted in a very different era. Statins were less widely used, many people smoked, blood pressure control was less aggressive, and baseline cardiovascular risk was higher. As prevention improved, the balance between benefit and harm began to shift.

The Three Trials That Changed Everything

In 2018, three large, contemporary randomized trials were published almost simultaneously. Together, they forced a reassessment of aspirin for primary prevention.

ASPREE: Healthy Older Adults

The ASPREE trial enrolled over 19,000 healthy older adults, mostly aged 70 years or older, with no prior cardiovascular disease. Participants were randomized to low-dose aspirin or placebo and followed for nearly five years. Importantly, although ASPREE included a substantial number of Australian participants, these were otherwise healthy individuals, without known cardiovascular disease or especially high cardiovascular risk. Their eligibility for the trial was simply based on their age.

Aspirin did not reduce cardiovascular events. It increased major bleeding. Unexpectedly, it was also associated with higher all-cause mortality, largely driven by cancer deaths.

This finding was unexpected and remains incompletely explained, as earlier observational data had suggested a possible cancer-preventive effect of aspirin.

Extended follow-up reinforced the central message that there is no cardiovascular benefit in this population.

ASCEND: People With Diabetes

The ASCEND trial studied over 15,000 people with diabetes but no known cardiovascular disease. Diabetes confers higher baseline cardiovascular risk, making this a population in whom aspirin might plausibly offer benefit.

There was a modest reduction in serious vascular events. Serious vascular events occurred in a significantly lower percentage of participants in the aspirin group (658 participants (8.5%)) than in the placebo group (743 participants (9.6%); rate ratio 0.88).

This corresponds to an approximate 12% relative reduction in serious vascular events over the trial period, with around 95 fewer such events in the aspirin group.

However, this benefit was almost exactly offset by an increase in bleeding. Major bleeding events occurred in 314 participants (4.1%) in the aspirin group, compared with 245 (3.2%) in the placebo group.

This translates to approximately 69 additional major bleeding events attributable to aspirin. Overall this was considered to be a net neutral effect.

ASCEND illustrated a recurring theme in modern prevention. Aspirin can reduce thrombotic events, but the accompanying bleeding risk largely negates that benefit.

Notably, participants were not stratified by imaging or plaque burden, with diabetes being the primary risk-defining feature.

ARRIVE: Moderate Cardiovascular Risk

The ARRIVE trial enrolled 12546 individuals considered to be at moderate cardiovascular risk based on traditional risk factors.

In practice, the observed event rate was much lower than expected, likely reflecting contemporary risk management and resulting in a population closer to low risk.

Aspirin did not significantly reduce cardiovascular events, while bleeding risk was increased.

ARRIVE highlighted an important limitation of many primary prevention trials. Risk estimation based on clinical factors alone is imprecise, and many enrolled participants ultimately turn out to be at relatively low absolute risk.

What These Trials Have in Common

The consistency across these studies is striking. Different populations, but similar conclusions. For most people without established cardiovascular disease, starting aspirin does not meaningfully reduce cardiovascular events and does increase bleeding risk.

There is another shared feature that deserves attention.

None of these trials required demonstration of coronary atherosclerosis for enrollment. Participants were selected using age and clinical risk factors, not imaging or direct evidence of plaque. Cardiovascular risk stratification was modest, and many participants likely had little or no coronary atheroma.

That matters when interpreting the results.

What About People Already Taking Aspirin?

This is where confusion often arises.

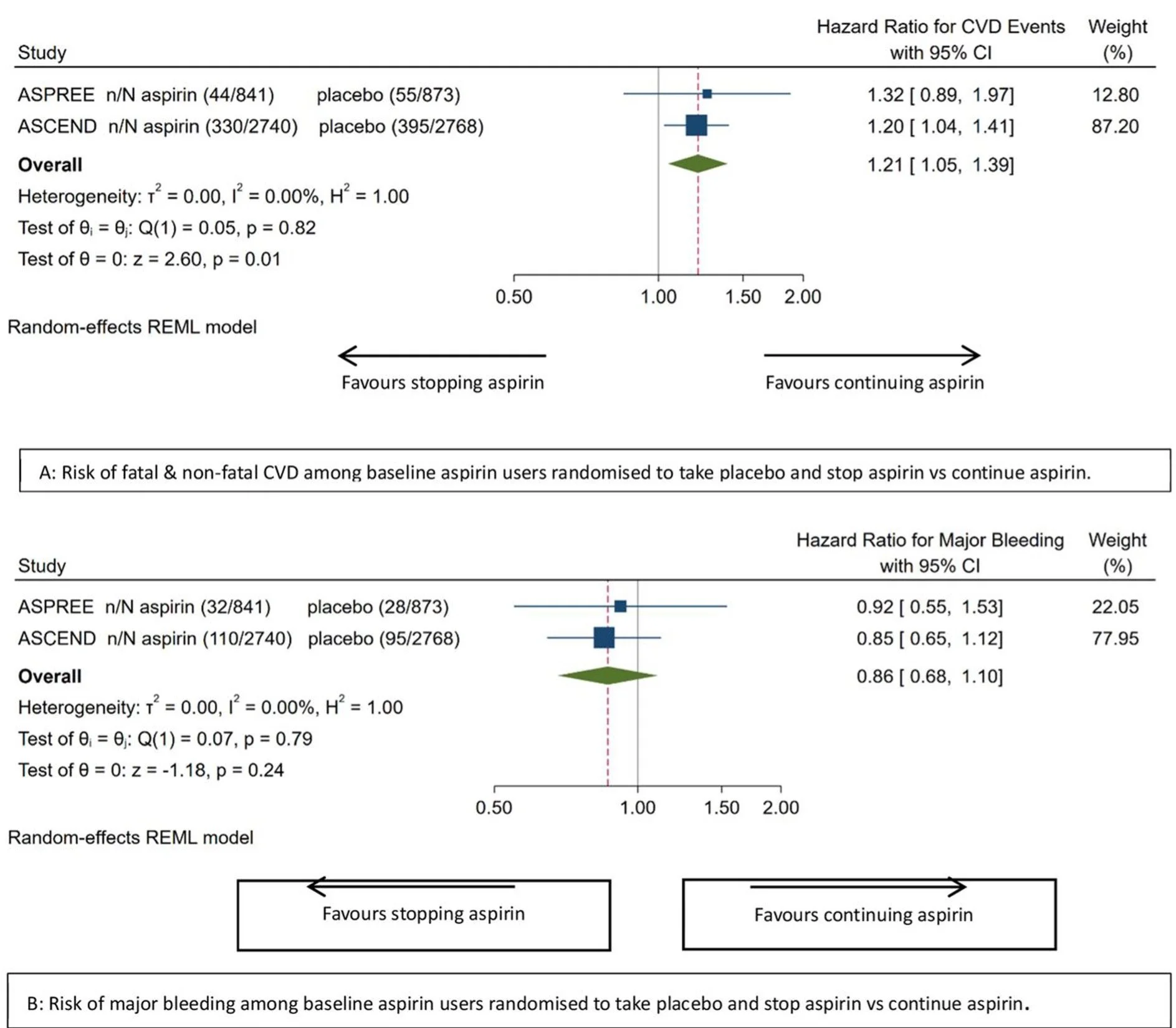

A meta-analysis of ASCEND and the ASPREE studies examined outcomes after aspirin discontinuation in participants who had been taking aspirin before enrolment. Those randomized to placebo and required to stop their aspirin, experienced an approximately 20% higher rate of cardiovascular events compared with those who continued aspirin (although their risk of bleeding did reduce). This excess risk appeared early and persisted over time, suggesting unmasking of aspirin’s antithrombotic protection rather than a rebound hypercoagulable state.

Meta-analytic effect of stopping vs continuing aspirin on ASCVD and major bleeding among baseline aspirin users. Publication

This observation does not overturn the original ASPREE findings. It does not justify starting aspirin in aspirin-naive individuals. But it does mean that stopping aspirin in those who are tolerating it without side effects should be a considered decision, particularly in older patients who have taken aspirin for many years without bleeding issues.

Can Coronary Calcium Scoring Help Identify People Who May Benefit From Aspirin?

One of the major limitations of the large aspirin trials is that participants were enrolled based on age and clinical risk factors, not on evidence of coronary atherosclerosis. Most did not undergo imaging, and many likely had little or no plaque.

Coronary artery calcium (CAC) scoring changes that. CAC is a direct measure of coronary atheroma burden and is one of the strongest independent predictors of future myocardial infarction and cardiovascular mortality. It provides incremental risk information beyond traditional risk calculators and allows reclassification of patients who otherwise appear to be at intermediate risk.

The Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand (CSANZ) has previously published a formal position statement on CAC scoring, emphasising its role in primary prevention and in guiding escalation of therapy when treatment decisions are uncertain.

In that statement, high cardiovascular risk is defined by a CAC score of 400 or higher, or a CAC score of 100 to 399 in individuals above the 75th percentile for age and sex. In these groups, the CSANZ recommends treatment with a high-efficacy statin and aspirin. At the time this was written, it is also considered reasonable to treat patients with CAC scores of 100 or higher with aspirin and statin therapy, while asymptomatic patients with a CAC score of zero are unlikely to benefit.

Reference:

Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand. CSANZ Position Statement on Coronary Artery Calcium Scoring, 2017.

https://www.csanz.edu.au/Common/Uploaded%20files/Smart%20Suite/Smart%20Library/14b9000c-9e90-43ba-a841-c2182f0500d0/CAC_Position-Statement_2017_ratified-26-May-2017.pdf

Importantly, very high calcium scores identify a group whose risk approaches that seen in secondary prevention.

Earlier modelling studies suggested a CAC threshold of 100 might justify aspirin use, but these analyses assumed relatively low bleeding rates. Contemporary data suggest that a higher CAC threshold, such as 300 or above, may better identify individuals in whom aspirin is likely to offer net benefit. A CAC score above 1000 is clearly associated with cardiovascular event rates comparable to patients with established coronary disease. In this setting, aspirin use is biologically and clinically plausible, as thrombotic risk is high and theoretically the balance of benefit and harm shifts in favour of Aspirin.

This approach reframes aspirin use away from broad population prevention and toward targeted therapy in people with demonstrable coronary disease.

Number needed to treat (NNT) and number needed to harm (NNH)

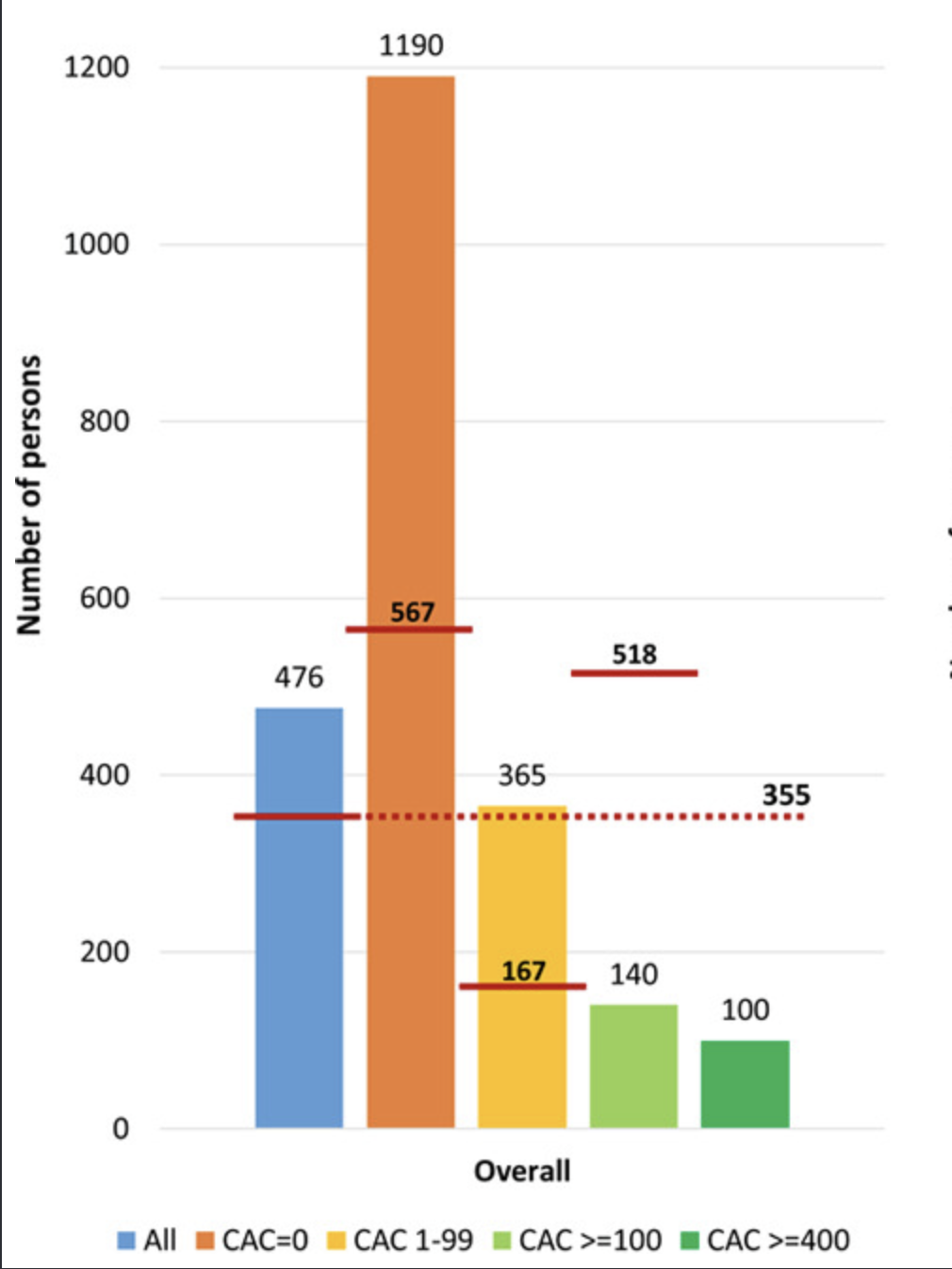

A useful way to visualise the trade-off between benefit and harm with aspirin in primary prevention is through number needed to treat (NNT) and number needed to harm (NNH) metrics, which show how many people would need to take aspirin over a defined period to prevent one cardiovascular event versus how many would experience a major bleed because of it. In a well-cited modelling analysis published in Circulation (Ridker et al.), investigators used contemporary estimates of event rates and aspirin effects to project these numbers across different baseline risk groups.

They found that in lower-risk primary prevention populations, with no imaging evidence of atherosclerosis, the NNH for major bleeding (355) was lower than the NNT to prevent a first cardiovascular event, meaning more people would be harmed by bleeding than helped by preventing an event. In contrast, when stratified by atherosclerotic burden, the balance shifts. For individuals with high coronary calcium or otherwise elevated risk, the projected NNT falls substantially, indicating that fewer people need to be treated to prevent an event, while the NNH remains relatively stable, meaning that the potential benefit of aspirin begins to outweigh the bleeding risk.

Number needed to treat with low-dose aspirin during 5 years to prevent 1 CVD event and number needed to cause a major bleeding event by baseline CAC score. If the CAC is greater than 100, the number needed to treat (140) is much lower than the number needed to harm (518). However for patients with CAC < 100, the NNT is very high, because the risk of an event is so low. Hence in this group, the NNH is lower, meaning that Aspirin is more likely to cause harm in this group.

This NNT/NNH framing helps explain why simple clinical risk factor scores in trials such as ASPREE, ASCEND, and ARRIVE failed to identify net benefit, while CAC-guided strategies — which enrich for a higher atherosclerotic burden — may identify subgroups in whom aspirin could reasonably be considered.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/epub/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.045010

Does Lipoprotein(a) Change the Equation?

Lipoprotein(a), often abbreviated as Lp(a), is a genetically determined cholesterol particle that increases the risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Unlike LDL cholesterol, Lp(a) levels are largely fixed from birth and are only modestly influenced by lifestyle or standard lipid-lowering therapies.

There is now strong genetic and epidemiological evidence that elevated Lp(a) is a causal cardiovascular risk factor. As a result, Lp(a) is increasingly recognised as a risk enhancer rather than a treatment target in its own right.

This has raised an important question. Could aspirin be more beneficial in people with elevated Lp(a), even if it offers little benefit on average in primary prevention?

Several observational and secondary analyses suggest this may be possible. In cohort studies and post-hoc analyses, regular aspirin use has been associated with substantially lower rates of coronary events and cardiovascular mortality among individuals with elevated Lp(a), commonly defined as levels above 50 mg/dL. In contrast, no clear benefit has been observed in those with normal Lp(a) levels.

These findings are biologically plausible. Lp(a) appears to promote both atherosclerosis and thrombosis, and aspirin's antiplatelet effects may be more relevant in this higher-risk, more pro-thrombotic setting.

There are important caveats. Like the calcium scoring papers, these data are not derived from randomized controlled trials and are vulnerable to confounding and selection bias. Current guidelines do not yet recommend aspirin for primary prevention solely on the basis of elevated Lp(a). Instead, Lp(a) should be considered as part of a broader risk assessment.

In selected individuals with elevated Lp(a), low bleeding risk, and other markers of increased cardiovascular risk, aspirin may be discussed as part of a personalised decision-making process.

Reference:

American College of Cardiology. An Update on Lp(a) and Aspirin in Primary Prevention.

https://www.acc.org/Latest-in-Cardiology/Articles/2024/07/17/14/02/An-Update-on-Lpa-and-Aspirin-in-Primary-Prevention

The Bottom Line

Aspirin is no longer a routine preventive therapy for people without cardiovascular disease. For many, the risks outweigh the benefits.

At the same time, stopping aspirin is not always trivial, particularly after long-term use if well tolerated. Decisions should be individualised, considering bleeding risk, overall cardiovascular risk, and patient preferences.

The future of cardiovascular prevention is not about one-size-fits-all recommendations. It is about identifying risk accurately, treating what matters most, and using medications where they are most likely to offer benefit. Coronary calcium scoring, CT coronary angiography, and emerging risk markers such as Lp(a) can help identify people with higher underlying risk, but they do not replace comprehensive cardiovascular risk evaluation.