Aspirin for Primary Prevention: What We Thought, What We Know Now, and What Still Matters

For decades, low-dose aspirin has been considered a simple and generally harmless way to reduce the risk of heart attack and stroke. As people aged, many were advised to take it "just in case", even if they had never had cardiovascular disease (CVD) such as heart attack or stroke.

In recent years that advice has changed. Not subtly, but fundamentally.

Aspirin remains one of the most misunderstood medications in cardiovascular prevention. Some people are still taking it unnecessarily. Others have stopped it abruptly and are confused by mixed messages. And many are asking a reasonable question: if aspirin was once considered protective, what happened?

To answer that, we need to look carefully at the evidence. Aspirin lowers clot-related events but increases bleeding risk. The decision to use aspirin comes down to weighing its ability to reduce cardiovascular events against its risk of causing bleeding.

Any decision to use aspirin involves balancing a reduction in cardiovascular events against an increased risk of bleeding.

Why Aspirin Seemed Like a Good Idea

Aspirin reduces platelet aggregation and lowers the risk of clot formation. Most heart attacks come from blood clots sticking to plaque in the heart arteries. In people who have already had a heart attack or stroke, this antithrombotic effect clearly saves lives.

This is known as secondary prevention, and aspirin remains a cornerstone of care. After a heart attack, most patients should take aspirin long term because the risk of recurrent cardiovascular events is high.

The assumption for many years was that this benefit would extend to people without established cardiovascular disease. If clots cause heart attacks, and aspirin reduces clots, then surely aspirin could prevent first events too.

Early studies supported that view, but they were conducted in a very different era. Statins were less widely used, many people smoked, blood pressure control was less aggressive, and baseline cardiovascular risk was higher. As prevention improved, the balance between benefit and harm began to shift.

The Three Trials That Changed Everything

In 2018, three large, contemporary randomized trials were published almost simultaneously. Together, they forced a reassessment of aspirin for primary prevention.

ASPREE: Healthy Older Adults

The ASPREE trial enrolled over 19,000 healthy older adults, mostly aged 70 years or older, with no prior cardiovascular disease. Participants were randomized to low-dose aspirin or placebo and followed for nearly five years. Importantly, although ASPREE included a substantial number of Australian participants, these were otherwise healthy individuals, without known cardiovascular disease or especially high cardiovascular risk. Their eligibility for the trial was simply based on their age.

Aspirin did not reduce cardiovascular events. It increased major bleeding. Unexpectedly, it was also associated with higher all-cause mortality, largely driven by cancer deaths.

This finding was unexpected and remains incompletely explained, as earlier observational data had suggested a possible cancer-preventive effect of aspirin.

Extended follow-up reinforced the central message that there is no cardiovascular benefit in this population.

ASCEND: People With Diabetes

The ASCEND trial studied over 15,000 people with diabetes but no known cardiovascular disease. Diabetes confers higher baseline cardiovascular risk, making this a population in whom aspirin might plausibly offer benefit.

There was a modest reduction in serious vascular events. Serious vascular events occurred in a significantly lower percentage of participants in the aspirin group (658 participants (8.5%)) than in the placebo group (743 participants (9.6%); rate ratio 0.88).

This corresponds to an approximate 12% relative reduction in serious vascular events over the trial period, with around 95 fewer such events in the aspirin group.

However, this benefit was almost exactly offset by an increase in bleeding. Major bleeding events occurred in 314 participants (4.1%) in the aspirin group, compared with 245 (3.2%) in the placebo group.

This translates to approximately 69 additional major bleeding events attributable to aspirin. Overall this was considered to be a net neutral effect.

ASCEND illustrated a recurring theme in modern prevention. Aspirin can reduce thrombotic events, but the accompanying bleeding risk largely negates that benefit.

Notably, participants were not stratified by imaging or plaque burden, with diabetes being the primary risk-defining feature.

ARRIVE: Moderate Cardiovascular Risk

The ARRIVE trial enrolled 12546 individuals considered to be at moderate cardiovascular risk based on traditional risk factors.

In practice, the observed event rate was much lower than expected, likely reflecting contemporary risk management and resulting in a population closer to low risk.

Aspirin did not significantly reduce cardiovascular events, while bleeding risk was increased.

ARRIVE highlighted an important limitation of many primary prevention trials. Risk estimation based on clinical factors alone is imprecise, and many enrolled participants ultimately turn out to be at relatively low absolute risk.

What These Trials Have in Common

The consistency across these studies is striking. Different populations, but similar conclusions. For most people without established cardiovascular disease, starting aspirin does not meaningfully reduce cardiovascular events and does increase bleeding risk.

There is another shared feature that deserves attention.

None of these trials required demonstration of coronary atherosclerosis for enrollment. Participants were selected using age and clinical risk factors, not imaging or direct evidence of plaque. Cardiovascular risk stratification was modest, and many participants likely had little or no coronary atheroma.

That matters when interpreting the results.

What About People Already Taking Aspirin?

This is where confusion often arises.

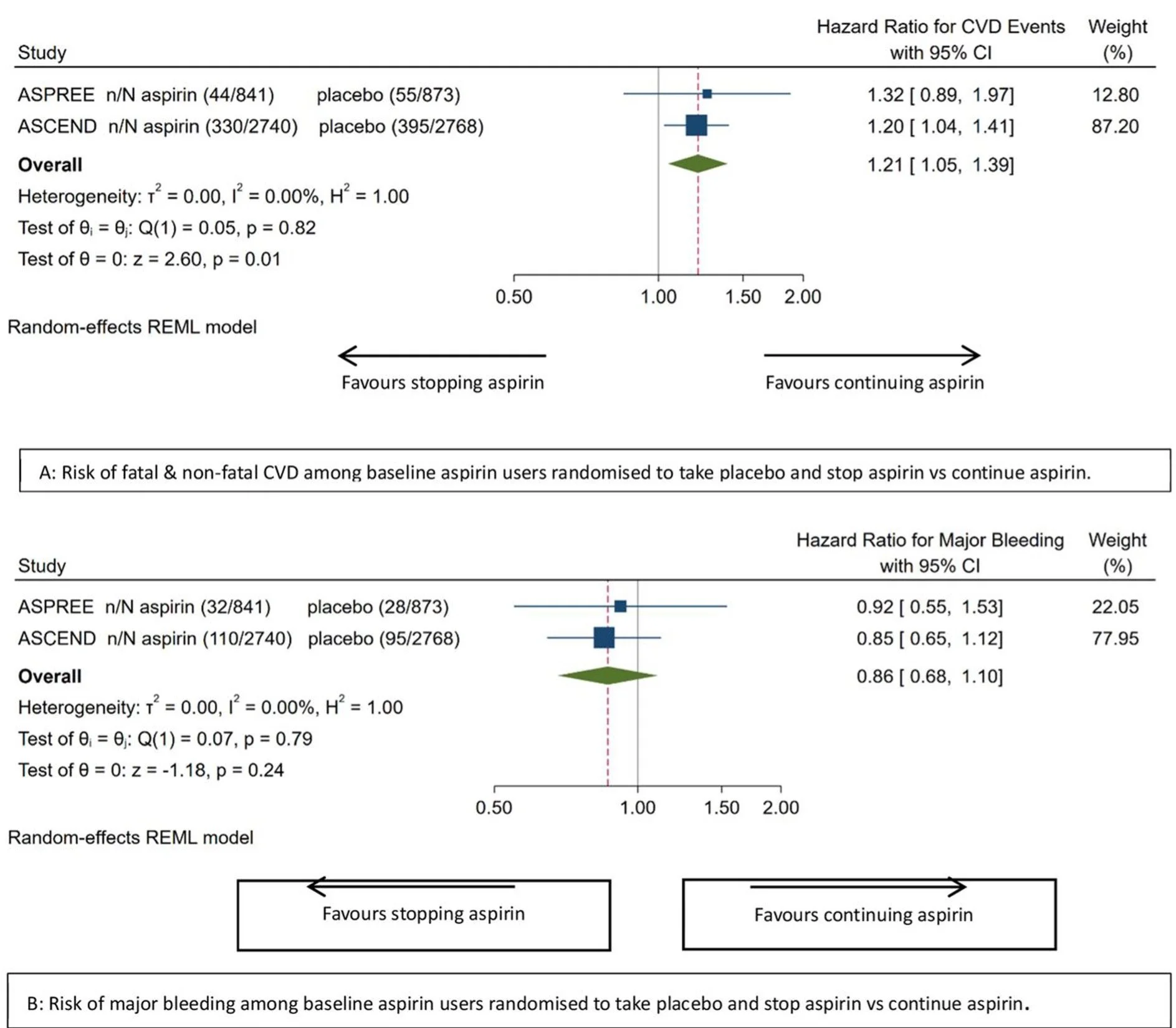

A meta-analysis of ASCEND and the ASPREE studies examined outcomes after aspirin discontinuation in participants who had been taking aspirin before enrolment. Those randomized to placebo and required to stop their aspirin, experienced an approximately 20% higher rate of cardiovascular events compared with those who continued aspirin (although their risk of bleeding did reduce). This excess risk appeared early and persisted over time, suggesting unmasking of aspirin’s antithrombotic protection rather than a rebound hypercoagulable state.

Meta-analytic effect of stopping vs continuing aspirin on ASCVD and major bleeding among baseline aspirin users. Publication

This observation does not overturn the original ASPREE findings. It does not justify starting aspirin in aspirin-naive individuals. But it does mean that stopping aspirin in those who are tolerating it without side effects should be a considered decision, particularly in older patients who have taken aspirin for many years without bleeding issues.

Can Coronary Calcium Scoring Help Identify People Who May Benefit From Aspirin?

One of the major limitations of the large aspirin trials is that participants were enrolled based on age and clinical risk factors, not on evidence of coronary atherosclerosis. Most did not undergo imaging, and many likely had little or no plaque.

Coronary artery calcium (CAC) scoring changes that. CAC is a direct measure of coronary atheroma burden and is one of the strongest independent predictors of future myocardial infarction and cardiovascular mortality. It provides incremental risk information beyond traditional risk calculators and allows reclassification of patients who otherwise appear to be at intermediate risk.

The Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand (CSANZ) has previously published a formal position statement on CAC scoring, emphasising its role in primary prevention and in guiding escalation of therapy when treatment decisions are uncertain.

In that statement, high cardiovascular risk is defined by a CAC score of 400 or higher, or a CAC score of 100 to 399 in individuals above the 75th percentile for age and sex. In these groups, the CSANZ recommends treatment with a high-efficacy statin and aspirin. At the time this was written, it is also considered reasonable to treat patients with CAC scores of 100 or higher with aspirin and statin therapy, while asymptomatic patients with a CAC score of zero are unlikely to benefit.

Reference:

Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand. CSANZ Position Statement on Coronary Artery Calcium Scoring, 2017.

https://www.csanz.edu.au/Common/Uploaded%20files/Smart%20Suite/Smart%20Library/14b9000c-9e90-43ba-a841-c2182f0500d0/CAC_Position-Statement_2017_ratified-26-May-2017.pdf

Importantly, very high calcium scores identify a group whose risk approaches that seen in secondary prevention.

Earlier modelling studies suggested a CAC threshold of 100 might justify aspirin use, but these analyses assumed relatively low bleeding rates. Contemporary data suggest that a higher CAC threshold, such as 300 or above, may better identify individuals in whom aspirin is likely to offer net benefit. A CAC score above 1000 is clearly associated with cardiovascular event rates comparable to patients with established coronary disease. In this setting, aspirin use is biologically and clinically plausible, as thrombotic risk is high and theoretically the balance of benefit and harm shifts in favour of Aspirin.

This approach reframes aspirin use away from broad population prevention and toward targeted therapy in people with demonstrable coronary disease.

Number needed to treat (NNT) and number needed to harm (NNH)

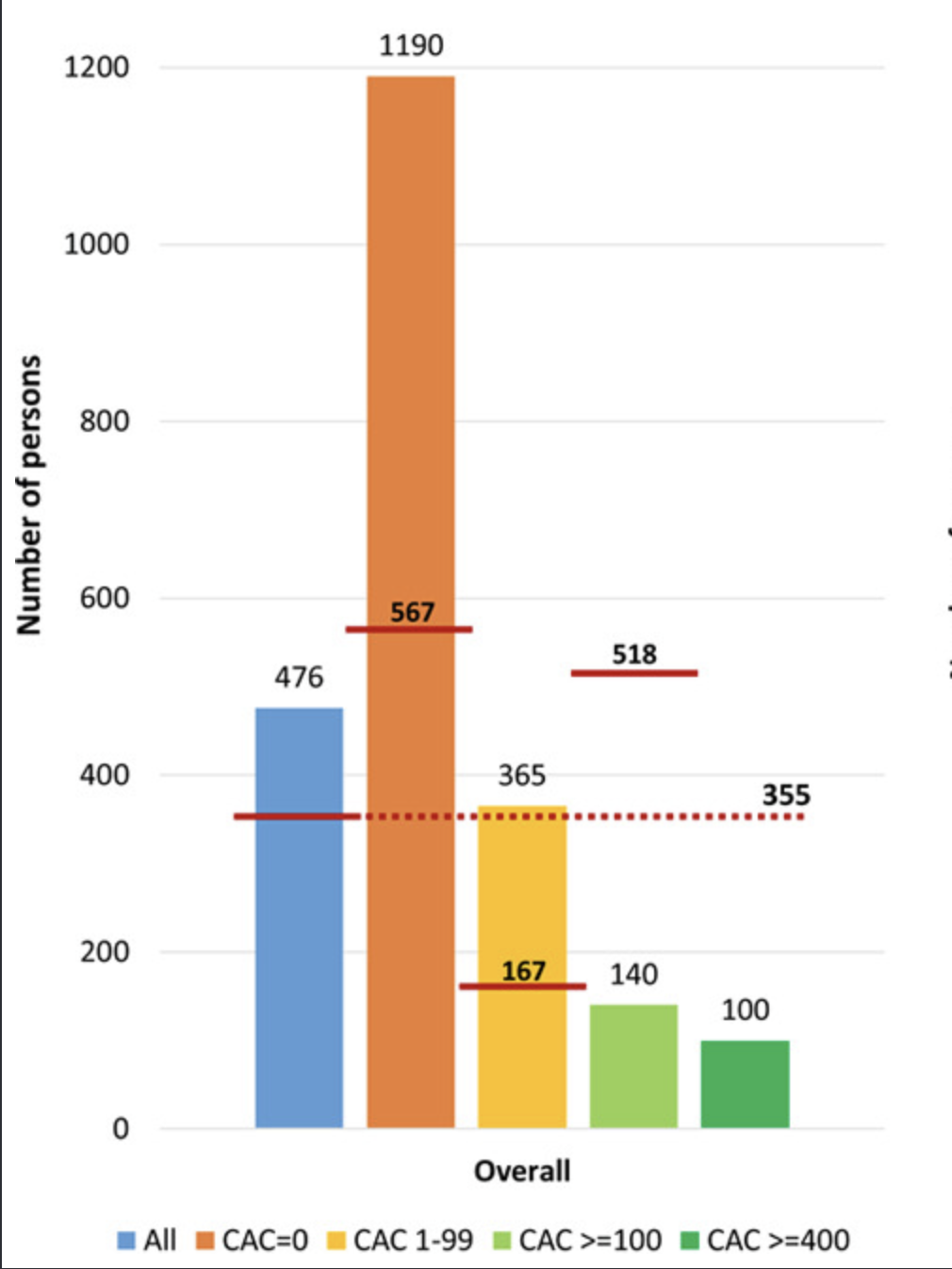

A useful way to visualise the trade-off between benefit and harm with aspirin in primary prevention is through number needed to treat (NNT) and number needed to harm (NNH) metrics, which show how many people would need to take aspirin over a defined period to prevent one cardiovascular event versus how many would experience a major bleed because of it. In a well-cited modelling analysis published in Circulation (Ridker et al.), investigators used contemporary estimates of event rates and aspirin effects to project these numbers across different baseline risk groups.

They found that in lower-risk primary prevention populations, with no imaging evidence of atherosclerosis, the NNH for major bleeding (355) was lower than the NNT to prevent a first cardiovascular event, meaning more people would be harmed by bleeding than helped by preventing an event. In contrast, when stratified by atherosclerotic burden, the balance shifts. For individuals with high coronary calcium or otherwise elevated risk, the projected NNT falls substantially, indicating that fewer people need to be treated to prevent an event, while the NNH remains relatively stable, meaning that the potential benefit of aspirin begins to outweigh the bleeding risk.

Number needed to treat with low-dose aspirin during 5 years to prevent 1 CVD event and number needed to cause a major bleeding event by baseline CAC score. If the CAC is greater than 100, the number needed to treat (140) is much lower than the number needed to harm (518). However for patients with CAC < 100, the NNT is very high, because the risk of an event is so low. Hence in this group, the NNH is lower, meaning that Aspirin is more likely to cause harm in this group.

This NNT/NNH framing helps explain why simple clinical risk factor scores in trials such as ASPREE, ASCEND, and ARRIVE failed to identify net benefit, while CAC-guided strategies — which enrich for a higher atherosclerotic burden — may identify subgroups in whom aspirin could reasonably be considered.

https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/epub/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.045010

Does Lipoprotein(a) Change the Equation?

Lipoprotein(a), often abbreviated as Lp(a), is a genetically determined cholesterol particle that increases the risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Unlike LDL cholesterol, Lp(a) levels are largely fixed from birth and are only modestly influenced by lifestyle or standard lipid-lowering therapies.

There is now strong genetic and epidemiological evidence that elevated Lp(a) is a causal cardiovascular risk factor. As a result, Lp(a) is increasingly recognised as a risk enhancer rather than a treatment target in its own right.

This has raised an important question. Could aspirin be more beneficial in people with elevated Lp(a), even if it offers little benefit on average in primary prevention?

Several observational and secondary analyses suggest this may be possible. In cohort studies and post-hoc analyses, regular aspirin use has been associated with substantially lower rates of coronary events and cardiovascular mortality among individuals with elevated Lp(a), commonly defined as levels above 50 mg/dL. In contrast, no clear benefit has been observed in those with normal Lp(a) levels.

These findings are biologically plausible. Lp(a) appears to promote both atherosclerosis and thrombosis, and aspirin's antiplatelet effects may be more relevant in this higher-risk, more pro-thrombotic setting.

There are important caveats. Like the calcium scoring papers, these data are not derived from randomized controlled trials and are vulnerable to confounding and selection bias. Current guidelines do not yet recommend aspirin for primary prevention solely on the basis of elevated Lp(a). Instead, Lp(a) should be considered as part of a broader risk assessment.

In selected individuals with elevated Lp(a), low bleeding risk, and other markers of increased cardiovascular risk, aspirin may be discussed as part of a personalised decision-making process.

Reference:

American College of Cardiology. An Update on Lp(a) and Aspirin in Primary Prevention.

https://www.acc.org/Latest-in-Cardiology/Articles/2024/07/17/14/02/An-Update-on-Lpa-and-Aspirin-in-Primary-Prevention

The Bottom Line

Aspirin is no longer a routine preventive therapy for people without cardiovascular disease. For many, the risks outweigh the benefits.

At the same time, stopping aspirin is not always trivial, particularly after long-term use if well tolerated. Decisions should be individualised, considering bleeding risk, overall cardiovascular risk, and patient preferences.

The future of cardiovascular prevention is not about one-size-fits-all recommendations. It is about identifying risk accurately, treating what matters most, and using medications where they are most likely to offer benefit. Coronary calcium scoring, CT coronary angiography, and emerging risk markers such as Lp(a) can help identify people with higher underlying risk, but they do not replace comprehensive cardiovascular risk evaluation.

Why do I need a holter monitor?

We may recommend the use of a Holter monitor to help diagnose or monitor certain heart conditions, particularly those affecting the heart rhythm. You may be wondering, “Why would I need a Holter monitor?” In this post, we will explain what a Holter monitor is, how it works, and why it is important for your care.

A Holter monitor is a small, portable device that continuously records your heart's electrical activity for 24 to 48 hours. It is similar to an electrocardiogram (ECG) but can record a longer period of time. The device consists of small electrodes that are attached to your chest and connected to a recording device, which can be worn on a belt or shoulder strap.

Holter monitors are used to diagnose and monitor heart conditions, such as arrhythmias, which are abnormal heart rhythms. These conditions may not be detected during a routine ECG or office visit, as they may occur intermittently. They can occur overnight, when you are asleep, and you may not be aware that they occur. A Holter monitor can capture any episodes of abnormal heart rhythms, which can help your cardiologist make an accurate diagnosis and develop a treatment plan.

A Holter monitor can also help your cardiologist evaluate the effectiveness of your treatments. For example, if you are taking medication for an arrhythmia, the Holter monitor can show whether the medication is controlling the abnormal rhythm or whether a change in medication or dosage is necessary.

The holter may be applied in our rooms, in a pathology practice, or even at a radiology / medical imaging practice. Once it is applied, you should go about your normal day. It is often useful to see the heart response to work, rest, stress, etc.

In summary, a Holter monitor is an important tool for diagnosing and monitoring certain heart conditions. The test is safe and painless.

If you have any further questions about Holter monitoring or your heart health, please do not hesitate to contact us

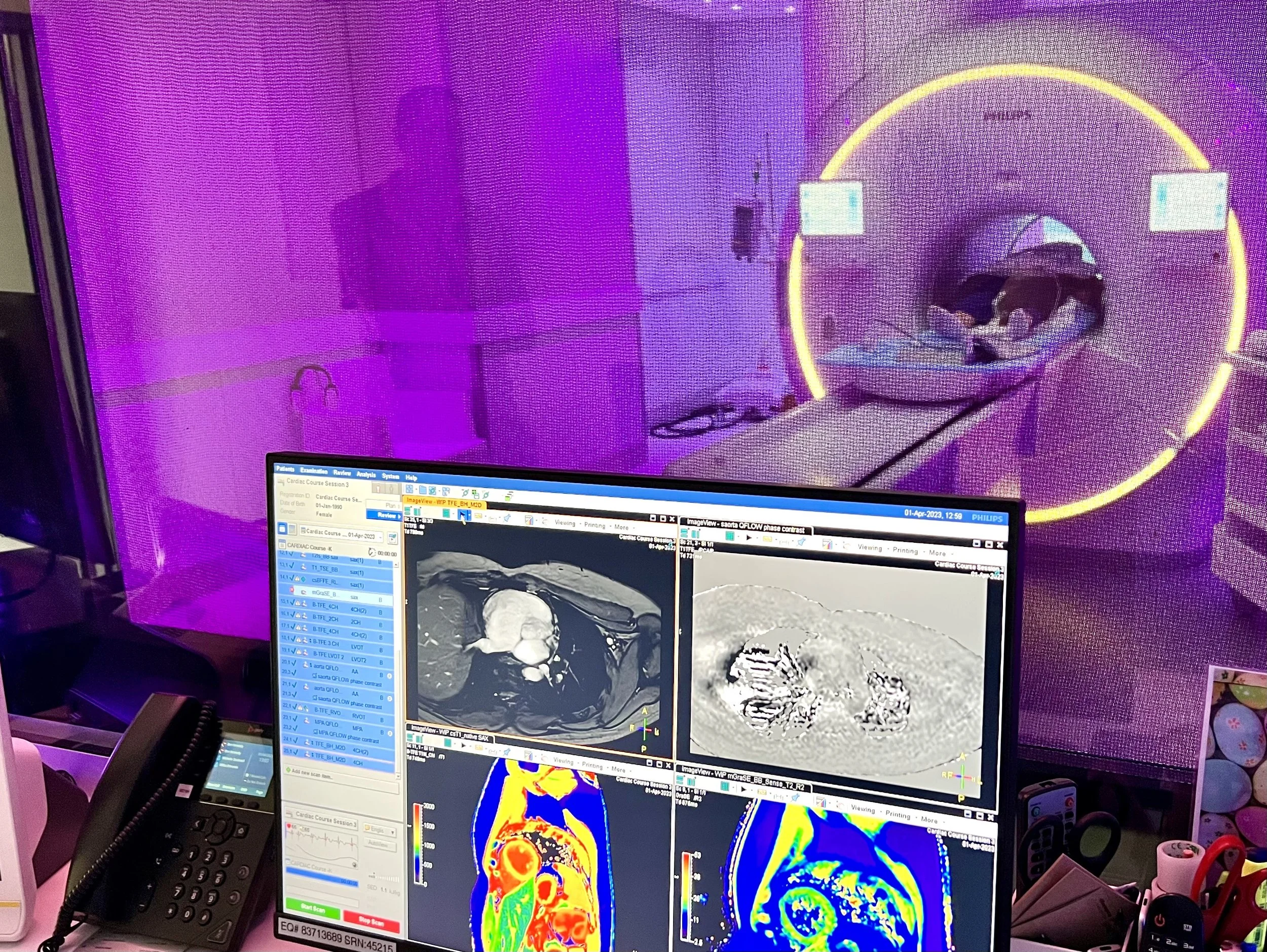

Can everyone have an MRI scan?

There are certain types of patients who cannot have an MRI scan (or may only have one with special preparation)s, due to safety concerns or technical limitations. These include:

Patients with pacemakers or other implanted electronic devices. The strong magnetic field of an MRI machine can interfere with these devices. This is often more prominent with stronger magnets (3 Tesla) than weaker magnets (1.5T). In the worst case scenario, this may cause harm to the patient. In some cases, patients with these devices may still be able to undergo an MRI scan with special precautions, but it will depend on the specific type of device, the type od scan required, the staff available and the MRI machine used.

Patients with loose metal in their body (particularly iron in the eyes): Patients with previous eye damage from metal or iron, such as can occur in welding or shot-blasting, may require eye X-rays before undergoing MRI. The metal can move during the scan and cause damage to the retina.

Patients with certain types of metal implants: Some metal implants, such as those made of iron or steel, can heat up, or move, inside the body during an MRI scan, causing tissue damage or other complications. Patients with these types of implants may need to avoid MRI scans or undergo alternative imaging tests. Joint replacements, cardiac stents, and most cardiac valve replacements are usually safe, because the metal is well anchored, but it is important to mention any implants to the radiographers before entering the scan room.

Patients with severe kidney problems / dialysis: Some MRI contrast agents can be harmful to patients with severely impaired kidney function. In these cases, doctors may need to use a different type of contrast agent or avoid using contrast altogether.

It's important to inform your doctor about any medical conditions, implanted devices, or pregnancy before undergoing an MRI scan to ensure your safety and the best possible imaging results.

Diets for cardiovascular health

Although medications are often the cornerstone of reducing cardiac risk, maintaining a healthy diet is an important part of maintaining heart health. Minimising processed food seems important. Eating a diet that is high in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, lean proteins, and healthy fats may help reduce the risk of heart disease, stroke, and other cardiovascular conditions.

The South Beach Diet and the Mediterranean diet are two popular eating patterns that have been shown to be beneficial for heart health. Both diets emphasize whole, unprocessed foods and encourage the consumption of healthy fats, lean proteins, and a variety of fruits and vegetables. In this blog post, we'll explore the South Beach Diet and the Mediterranean diet in greater detail and discuss their potential benefits for heart health

The South Beach Diet

Invented by Arthur Agatston

The South Beach Diet is a popular low-carbohydrate diet that was created by cardiologist Dr. Arthur Agatston, who also invented the Agatston score used in CT calcium scoring. Here's a summary of the diet:

Phase 1: In the first phase, which lasts for two weeks, carbohydrates are limited to 20 grams per day. This phase is designed to kick-start weight loss and help stabilize blood sugar levels. During this phase, dieters eat lean proteins, non-starchy vegetables, nuts, and low-fat dairy products.

Phase 2: In the second phase, which lasts until the desired weight loss is achieved, carbohydrates are gradually reintroduced into the diet. This phase emphasizes whole grains, fruits, and starchy vegetables. The goal is to find the individual's carbohydrate tolerance level while continuing to lose weight.

Phase 3: In the third phase, which is the maintenance phase, dieters continue to follow the healthy eating habits they learned in the first two phases. The goal is to maintain the desired weight loss while enjoying a balanced diet that includes all food groups in moderation.

The South Beach Diet also encourages dieters to eat healthy fats, such as olive oil and avocado, and to avoid processed foods and sugary drinks. The diet emphasizes lean proteins, healthy fats, and low glycemic-index carbohydrates. It has been shown to be effective for weight loss, reducing inflammation, improving cholesterol levels, and reducing the risk of heart disease and diabetes.

The Mediterranean Diet

The Mediterranean diet is a heart-healthy eating pattern that is rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, seeds, and healthy fats, such as olive oil and fatty fish. Here's a summary of the Mediterranean diet for cardiovascular benefits:

Emphasis on plant-based foods: The Mediterranean diet places a strong emphasis on consuming plant-based foods, such as fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, and seeds. These foods are high in fiber, vitamins, and minerals that can reduce inflammation and improve heart health.

Healthy fats: The diet includes healthy fats, such as olive oil, nuts, seeds, and fatty fish. These healthy fats are beneficial for cardiovascular health because they can help reduce inflammation and lower cholesterol levels.

Limited red meat: Red meat is limited on the Mediterranean diet, and is replaced with lean protein sources, such as fish, poultry, and plant-based proteins like beans and lentils. The red meat consumed in the original studies of this diet was lean, gamey meat, such as rabbit and goat, rather than beef, lamb, or pork. Proponents of this diet suggest that reducing the intake of red meat can reduce the risk of heart disease.

Moderate alcohol intake: The Mediterranean diet also includes moderate alcohol intake, usually in the form of red wine. However, it's important to note that excessive alcohol intake can have negative health effects, so moderation is key.

Reducing processed foods: The Mediterranean diet emphasizes consuming whole, unprocessed foods, and reducing the intake of processed and sugary foods. This can improve heart health by reducing inflammation and maintaining healthy blood sugar levels.

Overall, the Mediterranean diet is a healthy eating pattern that can promote heart health by reducing inflammation, improving cholesterol levels, and maintaining healthy blood sugar levels. It is associated with a lower risk of heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes

What is involved in having an echocardiogram?

Echocardiogram (Cardiac Ultrasound)

An echocardiogram, also known as a cardiac ultrasound, is a non-invasive test that allows doctors to assess the structure and function of the heart. The test uses high-frequency sound waves to create detailed images of the heart and its surrounding blood vessels, and is similar to the scans used during pregnancy.

What can I expect:

During an echocardiogram, you will be asked to lie down on a table while the sonographer applies a special gel to your chest and presses (often quite firmly) with an echo probe (see below). This gel helps the sound waves travel more easily and produces clearer images of the heart. You will usually be required to remove clothing from the upper part of the body for this test. Hospital gowns and sheets are available to maintain modesty.

The sonographer places a small device called a transducer, or echo probe, on your chest. The transducer sends out sound waves and picks up the echoes that bounce back from the heart. These echoes are then converted into images that can be seen on a screen.

The sonographer may ask you to change positions or hold your breath during the test to obtain different views of the heart. The test usually takes about 30 - 45 minutes to complete.

Why it's Done:

An echocardiogram can help diagnose or evaluate a variety of heart conditions, including:

Heart valve disease, such as leaky or narrowed valves

An enlarged heart (dilated cardiomyopathy)

Heart failure

Congenital heart defects

Increased wall thickness (from hypertensive heart disease or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy)

Problems with the systolic function (pumping) or diastolic function (relaxing) of the heart's muscle

Evaluate a dilated aortic root or ascending aorta

Risks:

Echocardiograms are considered very safe and do not involve any radiation exposure. The test is non-invasive and does not require any incisions or injections. The gel applied to your chest may feel cold or sticky, but it is not harmful. The sonographer may need to press firmly, which can be uncomfortable.

After the Test:

Once the echocardiogram is complete, you will be able to resume your normal activities straight away. The results of the scan are often available soon after the test and your cardiologist will review the images and discuss the results with you. This may be on the day of the scan or at a follow-up appointment. In some cases, you may receive a letter detailing the results and follow up. Additional testing or treatment may be recommended based on the results of the test.

Conclusions:

An echocardiogram is a valuable and safe diagnostic tool that can help doctors assess the structure and function of the heart muscle, valves and nearby structures. The test is non-invasive and relatively quick, making it a convenient option for many patients.

If you have any questions or concerns about the test, please don’t hesitate to call the rooms.

Checking blood pressure at home

Why should I measure my BP at home?

Home blood pressure (BP) monitoring is the self-measurement of BP in the your usual environment, at home, at work or in-between. This provides a number of BP readings that are more reliable for assessment of true underlying BP than a single measurement obtained in the clinic. The readings can be taken on multiple days, and therefore this is complementary to 24-hour ambulatory BP, and is likely to be better for the diagnosis and management high or low blood pressure.

What type of device should I use?

The BP measurement device should use an appropriately sized arm cuff, rather than a wrist cuff, and ideally should be validated and automated. I have written a seperate article about choosing a BP cuff that is also available on this website here.

When should I check my BP?

There are different schools of thought on how best to assess home BP.

For many patients, I will ask that you assess the BP randomly throughout the day. Check at breakfast time one day, then dinner time the next. This gives an estimate of BP control at different times throughout the day, and mimics a 24 hour BP monitor test.

However the official guidelines suggest a more standardised approach.

Heart Foundation Guidelines on Home BP Assessment

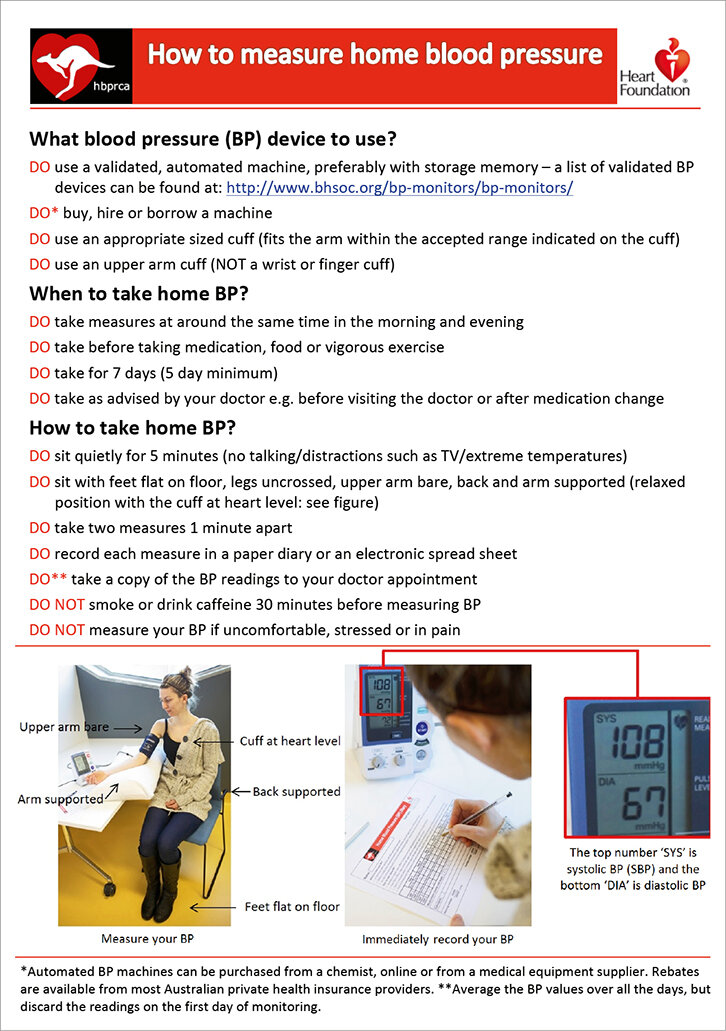

How should I check my BP?

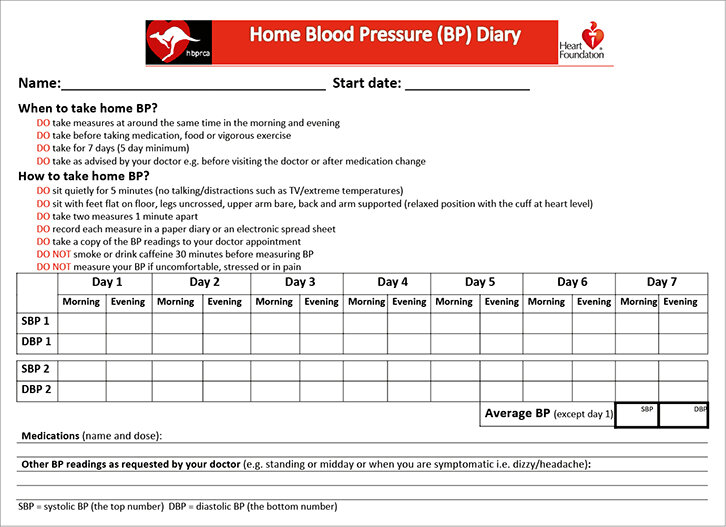

The Heart Foundation advice is that a patient should measure their BP at around the same time in the morning and the evening, before medication over a period of seven days. BP should be checked after going to the toilet but before food, caffeine or vigorous exercise, as all these can affect BP.

In order to achieve “standard” measurements, it is suggested that two BP measurements should be taken in a quiet room after five minutes of seated rest with feet on the floor, and the two readings taken one minute apart. The actual advice is as follows, “The patient should be in the seated position with feet flat on the floor, legs uncrossed, upper arm bare, back supported and arm supported in a relaxed position with the cuff at heart level”. The BP should be recorded immediately in a diary.

It is worth noting that late morning / lunch-time readings may also provide information for optimising the timing of medications (for example morning versus evening), and so I often ask for these too. If necessary, a formal 24-hour ambulatory BP monitor can provide further information where necessary.

This process (the sitting down in a standard position within a quiet room) ensures that we are recording the lowest possible BP, in a reproducible manner. If following this approach, the readings could be recorded in a home BP diary, such as the downloadable one below.